By Tehmina Kazi

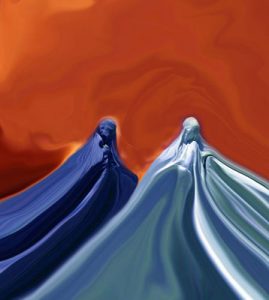

Unlike other articles on Muslim women’s sartorial trends, this one will not start with a terrible “thinly-veiled” pun, or a picture of a woman with her face covered in black cloth.

Shazia Hobbs managed to avoid both these traps in her “Ban the burqa” article, which correctly identified religious fundamentalism as a bigger problem in the current generation of British Muslims, than in previous generations. The proliferation of face-veils is simply one manifestation of this; other manifestations include gender segregation on university campuses, and the ex-communication (or takfir) of dissenting voices in Muslim communities.

However, my objections to the face-veil are somewhat different from Hobbs’, and I disagree with her conclusion that it should be banned completely in public places.

Niqabs are not the sole preserve of women who “are married to, or are the daughters of, men with beards.” A 2013 Cambridge University study, “Narratives of Conversion to Islam in Britain: Female Perspectives”, found that there was considerable pressure on female converts to cover their faces in Salafi circles. Kevin Brice’s 2010 research for Faith Matters, “A Minority within a Minority,” shows that 5% of female converts had worn a face-veil at some point.

It is true that the most popular media representation of niqabis (at least in recent years, after the hordes of Gulf tourists in Kensington) is black-clad women wielding “Death to those who insult Islam” and “Sharia for Britain” banners. It is no secret that these women belonged to the now-banned extremist group Al-Muhajiroun. British Muslims for Secular Democracy became the first Muslim organisation to challenge this group publicly, at a Piccadilly Circus demo in 2009.

However, UK niqabis have a wide range of political affiliations – and none, of course. The niqabi media spokespeople I have met have been associated with groups from iERA to the Muslim Council of Wales. A representative of the latter proceeded to continually interrupt me on BBC The Big Questions in January 2016, when we discussed British Islam as front-row guests.

Speaking of TV interruptions, the religious scholar Khola Hasan’s experience of niqabis — a whole Channel 4 studio-full, no less — summed up a lot of my issues with this garment, and the arrogance of several of those who wear it. After the debate, Hasan (herself a devout Muslim who wears a headscarf) highlighted the hypocrisy and aggressiveness of the niqabi women in the audience:

“Interestingly, the niqabis clapped when someone on the panel was speaking. I was under the impression that according to Salafi thought, clapping is not permitted. As I tried to walk away from one woman, she grabbed my sleeve and tried to rip it off.”

If niqab really is a free choice and about pleasing God, as niqab advocates claim, then why is a refusal to wear it so often associated with bullying and intimidation? The answer is that all modesty doctrines rely on a degree of coercion, or at a more subtle level, a phenomenon known as adaptive preferences.

This is where an individual has to make a choice from a list of less-than-desirable options, and rather than facing up to the fact that these options are not ideal, they adopt the least bad one as part of a trade-off. For example, a woman might don a face-veil so that her parents will allow her to go to university and study, or a convert woman might start wearing a niqab to be seen as an “authentic” member of her local Muslim community, and receive greater respect as a result.

It goes without saying that these rights and freedoms should exist automatically, regardless of what a woman wears, but this position seems to be light-years away. Indeed, many advocates of the niqab often co-opt the language of human rights when a substantial proportion do not really believe in contemporary human rights norms, and would never publicly advocate for the rights of communities with whom they might disagree, for example ex-Muslims or LGBT people.

In my view, the debate should focus on the more pernicious implications of modesty doctrines — which includes female voices being seen as “temptations,” and excluded from the public space accordingly, and women’s (but not men’s) faces and identities being treated as a body part that should be hidden in public — rather than the positions of individual niqabis.

I still maintain that it is possible to have good relations with women who wear niqab, oppose total bans of it on civil libertarian grounds — BMSD has only called for restrictions of the face-veil in certain settings, where security or child protection considerations are invoked — and robustly challenge the religious rationale behind the face-covering (and even head-covering) in Muslim communities.

A good example of this robust challenge is Rabiha Hannan’s book, “Islam and the Veil,” which features essays from many contributors. One Islamic scholar’s essay states that, in his opinion, it is not even necessary for Muslim women to cover their hair, let alone their faces.

I long for the day when these opinions attract a critical mass of support among British Muslims, and their purveyors are not routinely demonised.

Tehmina Kazi is a human rights activist and writer based in Cork, Ireland. Tehmina was the Director of registered charity British Muslims for Secular Democracy from May 2009 to August 2016, where she worked to raise awareness of secularism among British Muslims and the wider public.

Tehmina Kazi is a human rights activist and writer based in Cork, Ireland. Tehmina was the Director of registered charity British Muslims for Secular Democracy from May 2009 to August 2016, where she worked to raise awareness of secularism among British Muslims and the wider public.

Contact her on TKazi83@yahoo.co.uk.

[…] Don’t ban the burqa – challenge the modesty doctrines instead […]